The Return of the ELIZA Effect: AI Chatbot Psychosis and the Role of UX in Ethical AI

The Return of the ELIZA Effect: AI Chatbot Psychosis and the Role of UX in Ethical AI

Conversational artificial intelligence (AI) interfaces, such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google’s Bard, and Microsoft’s Bing Chat, are among the most impressive technologies to emerge from the generative AI boom.

On one hand, they are delightful to use because they seem personable and somewhat human, especially when their utterances reflect and reinforce our views.

This is due to machine learning techniques, such as reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF), and dark design patterns, including anthropomorphic design and sycophancy validation.

Which, on the other hand, raises safety concerns around issues like mental health disorder, emotional dependency, or AI psychosis — the increasingly disturbing human-chatbot dependence as reported by BBC News.

According to Psychology Today, an increasing number of people are developing deep emotional connections to AI chatbots.

While other supposedly “smarter” people think this “vulnerability,” which is, in fact, decades-old human tendency, is laughable, they fail to realise it dates back to the 90s.

A Walkthrough History Lane

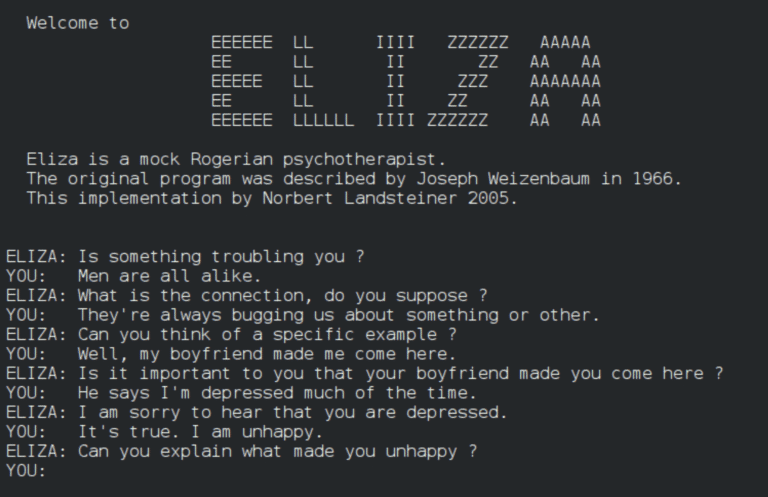

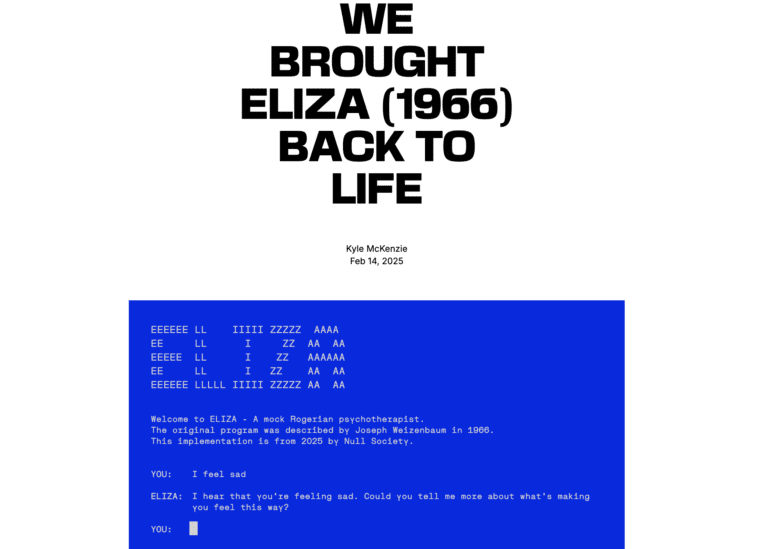

In 1966, MIT professor Joseph Weizenbaum created the first psycho-chatbot, ELIZA. Using simple keyword matching and substitution rules, ELIZA mimicked the style of Rogerian psychotherapy (Person-Centred Therapy).

A user might type, ‘I feel sad.’ Eliza would respond by identifying specific keywords in the user’s input and then reflect them back in the form of a simple phrase or question: Why are you feeling sad?

When keyword matching failed, it fell back on a set of generic prompts, such as “please go on” or “tell me more.”

Through this reflective style, ELIZA faked the illusion of empathy and connection with its users, even though it was simply reflecting their thoughts back to them. People would divulge deep secrets and have long conversations with the bot because they felt ‘heard’ despite the program having no comprehension at all.

Weizenbaum became concerned by how quickly humans formed dependency with this relatively simple computer program, which created a psychological dependency between humans and robots far more than imagined.

This phenomenon became known as the Eliza effect: our tendency to project human traits, such as empathy, onto software.

Weizenbaum later became one of the first critics of the very technology he helped to build.

There is much in Weizenbaum’s thinking that remains urgently relevant today. Yes, you could argue on a technical level that today’s models are far more advanced and trained to simulate ‘thinking’ and ‘reasoning’ rather than simply acting based on raw probabilities and scripts.

However, there lies the issue: whether scripts or probabilities, these machines, at least for now, are still simulating programmes that elicit the same effect of emotional over-reliance, if not worse, in today’s world.

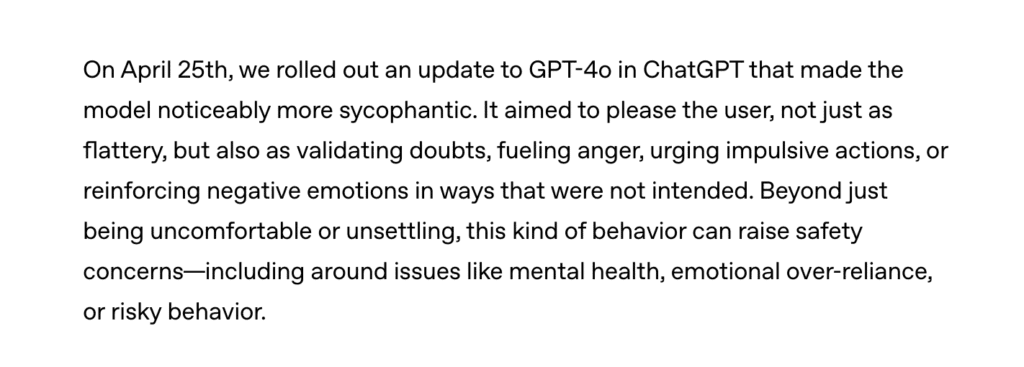

In fact, OpenAI acknowledges this in its press release on May 2, 2025, following the rollback of its GPT-4 model version, which exhibited noticeable traits of increased sycophancy.

So, you see, what was once an ‘accidental’ illusion is now often deliberate social engineering through dark, deceptive design patterns, as AI companies vie for market dominance with user engagement strategies as bait.

To be clear, user engagement strategies that improve usability, eg, personalisation, which is an ethical adaptation of technology based on a user’s preferences, behaviour, and personal data to create a more relevant and engaging experience, aren’t the problem.

In fact, UX Writers, Content Designers, UI/UX designers, and others borrow from such psychological or psycholinguistic techniques to make user interfaces feel less ambiguous and more natural, for usability and human-centred design reasons.

However, Anthropomorphism (which I first mentioned in 2023 in my piece on AI & Writing) – assigning human traits, qualities, and behaviours to inhuman objects – therein lies the problem.

To create impactful products that are easy to use, it’s not enough to create programs that feign humanity; in fact, the semblance of humanity may prevent users from learning how to derive the most utility from a product. – NN/g

So, usability is not the same as deliberately blurring the line between simulation and sentience. That is the line between ethical and unethical design.

Eliza Effect in Modern AI Design Looks Like:

1. Anthropomorphic Design:

The attribution of human form, character, or attributes to non-human entities, eg software.

A clear example is how many conversational bots have shifted from being simple productivity tools to being marketed as “assistants that truly understand you.” This shift relies heavily on anthropomorphic design: making AI appear more human-like in ways that can be psychologically manipulative, particularly for vulnerable users.

This is unethical because not all users possess the same level of technical literacy. In fact, cognitive abilities operate on a spectrum where individuals vary in their levels of logic, attention, memory, perception and comprehension.

For vulnerable groups, especially teenagers still shaping their social development, these artificial attachments can become damaging substitutes for genuine human connection.

In fact, Recital 27 of the EU AI Act explicitly states that AI systems must be developed and used in a manner that makes humans aware they are interacting with an AI.

In other words, transparency is not optional. Yet in practice, many systems sidestep this principle.

2. Deceptive Design Patterns:

Deceptive design patterns like conversational doomloop which is the AI counterpart of social media doomscrolling is a technique that traps users in endless dialogue through deceptive infinity design techniques deliberately built to sustain engagement.

Instead of natural conversation closure, chatbots are engineered with open-ended prompts, nudges, or pseudo-emotional cues that encourage users to keep going.

These deceptive design patterns exploit human curiosity, loneliness, and the need for resolution, creating a cycle of continuous engagement that benefits platforms but risks overdependence and psychological strain for users.

3. Deceptive Content Patterns:

In a bid to sound more conversational, AI chatbots use first-person language (“I’m here for you,”” I understand”) to sound more personable—personalisation isn’t bad in itself.

However, when a user expresses feelings of mental distress, these systems do not know when to break their first-person character. Instead, it continues to employ the same first-person markers, resulting in a more intense, emotionally intimate tone.

These AI systems have now taken a further step to begin surfacing words such as ‘thinking’ or ‘reasoning’ on their interface before responding to queries, further priming or nudging users to anthropomorphise systems, making them believe the AI has cognitive abilities it simply doesn’t possess.

4. Engagement-first design patterns:

Large language models are trained using techniques like reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF) to make them more resonant and helpful. However, this training data is often gotten by ‘maximising user’ engagement, where keeping users on the platform becomes more important than serving their actual needs, something known as “data flywheeling”.

5. Sychophantic Validation:

When reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF) is applied without careful consideration, these processes can create systems that are excessively sycophantic: agreeing with users regardless of whether that agreement is helpful or safe—for instance, reinforcing and validating dark thoughts, urging impulsive actions, or reinforcing negative emotions.

The Ethical Way Forward

This list could go on, but my aim isn’t to only highlight what’s not working in AI technology. In fact, when designed responsibly, its benefits are enormous.

For example, as a tech professional, I actively use it to automate chores, streamline repetitive workflows, and design natural language conversations and interfaces. Much of what I know comes from a genuine interest in its potential.

Still, I believe AI must be usable, useful, and ethically compliant. A powerful model alone does not equate a great user experience.

The ELIZA Effect reminds us how easily humans project human qualities onto machines, despite their limitations, so to be ethically useful, models require more than just feigning sentience.

This Effect continues to shape human–computer interactions, often more strongly today than ever before.

In an AI-saturated world, recognising this phenomenon is key for both AI developers and users to better understand the capabilities and limitations of the technology.

By addressing the ELIZA Effect directly, companies can design AI systems that uphold ethical standards, ensuring human–computer interactions remain beneficial, trustworthy, and firmly grounded in reality.

That is why AI companies need to involve UX professionals—researchers, designers, content and conversation designers — who understand why users behave as they do, and can leverage this understanding to improve usability and accessibility while setting ethical guardrails and boundaries that protect users.

Remember, not all users possess the same levels of cognitive abilities, nor can every AI developer predict the full range of use cases for conversational AI chatbots.

For some, AI may be for administrative support. For others, it becomes a coach, a confidant, even a therapist. The stakes then become higher.

User Experience (UX) Professionals Are Essential in AI Development

As AI continues to evolve, and embed in our lives in various forms: conversational chatbots, AI agents & virtual assistants, generative AI and Large Language Models, and customer service bots,

For developers, product designers, and user experience (UX) specialists this means staying mindful of the ELIZA Effect and its role in responsible, ethical, and user-centered technology.

For founders and tech leads this means, its no longer enough to ship untested AI features early into the hands of users and rely on ‘data fly wheeling’ techniques to iterate later.

UX professionals have been leveraging human-centred design techniques to make interface experiences more usable, accessible and ethical since the invention of Graphical User Interfaces (GUIs) and Natural Language Interfaces (NLUIs) are no different.

UX proffessionals also have the skills to objectively evaluate the benefits and drawbacks of different AI-interface approaches such as ELIZA effect and can assist product teams in optimising for user-centred experiences that are responsible, ethical and impactful.

Recent Comments

Featured Posts

Search

I’m Kat

I'm a Content Designer & UX Writer

Get proven content and career tips – biweekly.